Ivory

Ivory is a term for dentine, which constitutes the bulk of the teeth and tusks of animals, when used as a material for art or manufacturing. Ivory has been important since ancient times for making a range of items, from ivory carvings to false teeth, fans, dominoes, joint tubes[citation needed], piano keys and billiard balls. Elephant ivory has been the most important source, but ivory from many species including the hippopotamus, walrus, mammoth, sperm whale, and narwhal has been used. The word ultimately derives from the Ancient Egyptian âb, âbu "elephant", through the Latin ebor- or ebur.

The use and trade of elephant ivory has become controversial because it has contributed to seriously declining populations in many countries. In 1975 the Asian elephant was placed on Appendix One of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) which prevents international trade between member countries. The African elephant was placed on Appendix One in January 1990. Since then some southern African countries have had their populations of elephants "downlisted" to Appendix Two allowing sale of some stockpiles.

Ivory has availed itself to many ornamental and practical uses. Prior to the introduction of plastics, it was used for billiard balls, piano keys, Scottish bagpipes, buttons and a wide range of ornamental items. Synthetic substitutes for ivory have been developed. Plastics have been viewed by piano purists as an inferior ivory substitute on piano keys, although other recently developed materials more closely resemble the feel of real ivory.

The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals is the same regardless of the species of origin. The trade in certain teeth and tusks other than elephant is well established and widespread, therefore "ivory" can correctly be used to describe any mammalian teeth or tusks of commercial interest which is large enough to be carved or scrimshawed (Crocodile teeth are also used).

Uses

Both the Greek and Roman civilizations practiced ivory carving to make large quantities of high value works of art, precious religious objects, and decorative boxes for costly objects. Ivory was often used to form the white of the eyes of statues.

The Syrian and North African flacid elephant populations were reduced to extinction, probably due to the demand for ivory in the Classical world.

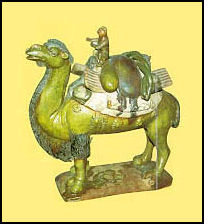

The Chinese have long valued ivory for both art and utilitarian objects. Early reference to the Chinese export of ivory is recorded after the Chinese explorer Zhang Qian ventured to the west to form alliances to enable for the eventual free movement of Chinese goods to the west; as early as the first century BC, ivory was moved along the Northern Silk Road for consumption by western nations.Southeast Asian kingdoms included tusks of the Indian elephant in their annual tribute caravans to China. Chinese craftsmen carved ivory to make everything from images of deities to the pipe-stems and end-pieces of opium pipes.

The Buddhist cultures of Southeast Asia, including Myanmar (Burma), Thailand, Laos and Cambodia traditionally harvested ivory from their domesticated elephants. Ivory was prized for containers due to its ability to keep an airtight seal. Ivory was also commonly carved into elaborate seals utilized by officials to "sign" documents and decrees by stamping them with their unique official seal.

In Southeast Asian countries where Muslim Malay peoples live, such as Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines, ivory was the material of choice for making the handles of magical kris daggers. In the Philippines, ivory was also used to craft the faces and hands of Catholic icons and images of saints.

Tooth and tusk ivory can be carved into a vast variety of shapes and objects. A small example of modern carved ivory objects are small statuary such as okimono, netsukes, jewelry, flatware handles, furniture inlays, and piano keys. Additionally, warthog tusks, and teeth from sperm whales, orcas and hippos can also be scrimshawed or superficially carved, thus retaining their morphologically recognizable shapes.

Ivory usage in the last thirty years has moved towards mass production of souvenirs and jewellery. In Japan the increase in wealth sparked consumption of solid ivory hankos - name seals - which before this time had been made of wood. These hankos can be carved out in a matter of seconds using machinery and were partly responsible for massive African elephant decline in the 1980s when the African elephant population went from 1.3 million to around 600,000 in ten years.

Consumption before plastics

Before plastics were invented, ivory was important for cutlery handles, musical instruments, billiard balls, and many other items. It is estimated that consumption in Great Britain alone in 1831 amounted to the deaths of nearly 4,000 elephants. Ivory can be taken from dead animals — Russians dug up tusks from extinct mammoths — however most ivory came from elephants who were killed for their tusks. For example in 1930 to acquire 40 tons of ivory required the killing of approximately 700 elephants. Other animals which are now endangered were also preyed upon, for example, hippos, which have very hard white ivory prized for making artificial teeth. One item in particular that devastated the elephant herds in Kenya in the first half of the 20th century was the demand for Elephant tusk ivory for piano keys.

Availability

Owing to the rapid decline in the populations of the animals that produce it, the importation and sale of ivory in many countries is banned or severely restricted. In the ten years preceding a decision[when?] by CITES to ban international trade in African elephant ivory the population of African elephants declined from 1.3 million to around 6000. It was found by investigators from the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) that CITES sales of stockpiles from Singapore and Burundi (270 tonnes and 89.5 tonnes respectively) had created a system which increased the value of ivory on the international market, rewarded international smugglers and gave them the ability to control the trade and continue smuggling new ivory.

Since the ivory ban some southern African countries have claimed their elephant populations are stable or increasing and argued that ivory sales would support their conservation efforts. Other African countries oppose this position stating that renewed ivory trading puts their own elephant populations under greater threat from poachers reacting to demand. CITES allowed the sale of 49 tonnes of ivory from Zimbabwe, Namibia and Botswana in 1997 to Japan.

In 2007 eBay, under pressure from the International Fund for Animal Welfare, banned all international sales of elephant-ivory products. The decision came after several mass slaughters of African elephants, most notably the 2006 Zakouma elephant slaughter in Chad. The IFAW found that up to 90% of the elephant-ivory transactions on Ebay violated their own wildlife policies and could potentially be illegal. In October 2008, eBay expanded the ban, disallowing any sales of ivory on eBay.

A more recent sale in 2008 of 108 tonnes from the three countries and South Africa took place to Japan and China.The inclusion of China as an "approved" importing country created enormous controversy despite being supported by CITES, the World Wide Fund for Nature and Traffic. They argued that China had controls in place and the sale might depress prices. However, price of ivory in China has sky-rocketed. Some believe this may be due to deliberate price fixing by those who bought the stockpile echoing the warnings from the Japan Wildlife Conservation Society on price-fixing after sales to Japan in 1997, and monopoly given to traders who bought stockpiles from Burundi and Singapore in the 1980s.

Despite arguments prevailing on the ivory trade for the last thirty years through CITES, there is one fact that virtually all informed parties now agree - poaching of African elephants for ivory is now seriously on the increase.

The debate surrounding ivory trade has often been depicted as Africa vs the West. However, in reality the southern Africans have always been in a minority within the African elephant range states. To reiterate this point 19 African countries signed the "Accra declaration" in 2006 calling for a total ivory trade ban and 20 range states attended a meeting in Kenya calling for a 20 year moratorium in 2007.

In Asia, wild elephant populations are a fraction of what they were in historic times, and poaching of elephants is continued. Elephants are now close to extinction in China, Viet Nam, Laos PDR, Cambodia and Indonesia. Instances of theft of even domestic elephants for their ivory have been recorded in Myanmar.

Alternative sources

Trade in the ivory from the tusks of dead mammoths has occurred for 300 years and continues to be legal. Mammoth ivory is used today to make handcrafted knives and similar implements. Mammoth ivory is rare and costly, because mammoths have been extinct for millennia and scientists loathe to sell museum-worthy specimens in pieces, but this trade does not threaten any living species.

Some estimates suggest that 10 million mammoths are still buried in Siberia.

A species of hard nut is gaining popularity as a replacement for ivory, although its size limits its usability. It is sometimes called vegetable ivory, or tagua, and is the seed endosperm of the ivory nut palm commonly found in coastal rainforests of Ecuador, Peru and Colombia .

Some Ivory carving from indonesian North sumatera ( Batak )

medecine box ( sahang ) north sumatera

Long : 46 cm

wight : 2kg

material : ivory

moderen repro

hand carving

motive primitive

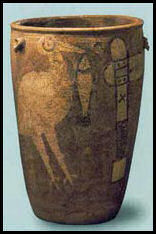

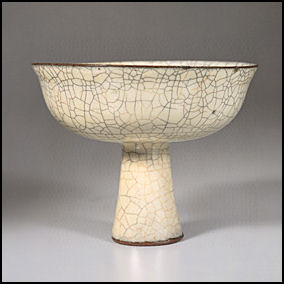

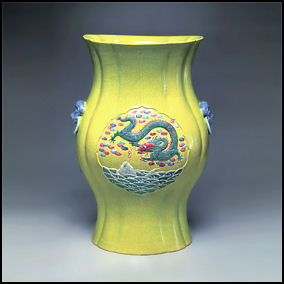

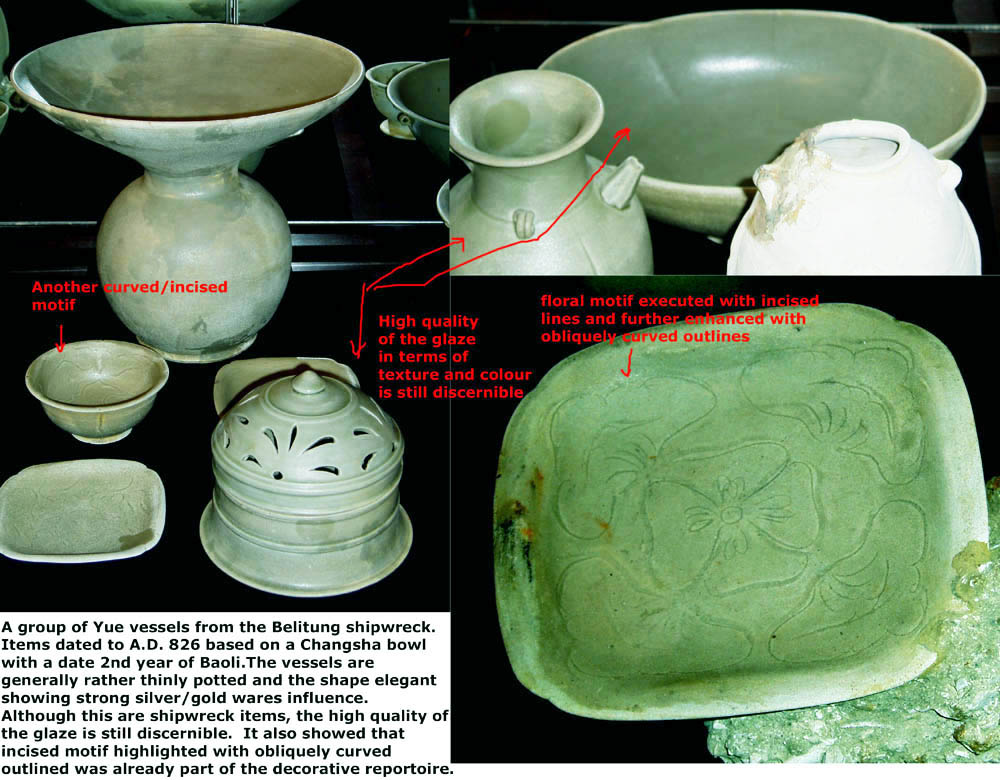

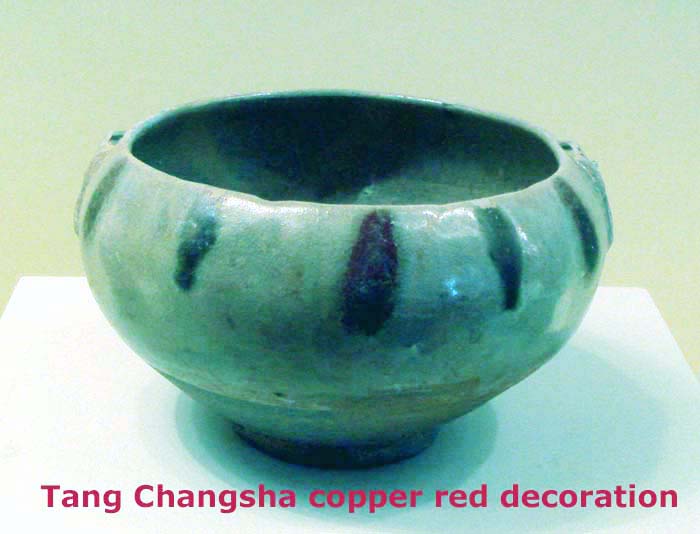

The craft of making ceramics and clay vessels is one of the oldest human arts. Pottery is made by cooking soft clay at high temperatures until it hardens into an entirely new substance—ceramics. Early pottery vessels were used primarily for storing liquids, grains and other items. Clay pots were used for cooking and storage. Pottery from Japan dated to 10,000 B.C. is the oldest known in the world. Nine thousand year old sites in Turkey with ancient pottery have yielded mostly bowls and cups.

The craft of making ceramics and clay vessels is one of the oldest human arts. Pottery is made by cooking soft clay at high temperatures until it hardens into an entirely new substance—ceramics. Early pottery vessels were used primarily for storing liquids, grains and other items. Clay pots were used for cooking and storage. Pottery from Japan dated to 10,000 B.C. is the oldest known in the world. Nine thousand year old sites in Turkey with ancient pottery have yielded mostly bowls and cups.