Batik

Batik (

/ˈbætɪk/ or

/bəˈtiːk/;

Javanese pronunciation: [ˈbateʔ];

Indonesian: [ˈbatɪk]) is a cloth that is traditionally made using a manual

wax-resist dyeing technique. Batik or fabrics with the traditional batik patterns are found in (particularly)

Indonesia,

Malaysia,

Japan,

China,

Azerbaijan,

India,

Sri Lanka,

Egypt,

Nigeria,

Senegal, and

Singapore.

Javanese traditional batik, especially from

Yogyakarta and

Surakarta, has notable meanings rooted to the Javanese conceptualization of the universe. Traditional colours include

indigo, dark brown, and white, which represent the three major

Hindu Gods

(Brahmā, Vishnu, and Śiva). This is related to the fact that natural

dyes are most commonly available in indigo and brown. Certain patterns

can only be worn by nobility; traditionally, wider stripes or wavy lines

of greater width indicated higher rank. Consequently, during Javanese

ceremonies, one could determine the royal lineage of a person by the

cloth he or she was wearing.

Other regions of Indonesia have their own unique patterns that

normally take themes from everyday lives, incorporating patterns such as

flowers, nature, animals, folklore or people. The colours of

pesisir

batik, from the coastal cities of northern Java, is especially vibrant,

and it absorbs influence from the Javanese, Arab, Chinese and Dutch

cultures. In the colonial times pesisir batik was a favourite of the

Peranakan Chinese, Dutch and

Eurasians.

[citation needed]

UNESCO designated Indonesian batik as a

Masterpiece of Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity on October 2, 2009. As part of the acknowledgment, UNESCO insisted that Indonesia preserve their heritage.

[

Etymology

Although the word's origin is

Javanese, its etymology may be either from the Javanese

amba ('to write') and

titik ('dot' or 'point'), or constructed from a hypothetical

Proto-Austronesian root

*beCík, meaning 'to tattoo' from the use of a needle in the process. The word is first recorded in English in the

Encyclopædia Britannica of 1880, in which it is spelled

battik. It is attested in the Indonesian Archipelago during the Dutch colonial period in various forms:

mbatek,

mbatik,

batek and

batik.

History

The carving details of clothes worn by

Prajnaparamita, 13th century East Java statue. The intricate floral pattern similar to traditional Javanese batik.

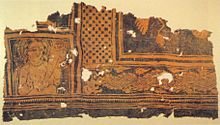

Wax resist dyeing technique in fabric is an ancient art form.

Discoveries show it already existed in Egypt in the 4th century BCE,

where it was used to wrap mummies; linen was soaked in wax, and

scratched using a sharp tool. In Asia, the technique was practised in

China during the

T'ang dynasty (618-907 CE), and in India and Japan during the

Nara period (645-794 CE). In Africa it was originally practised by the

Yoruba tribe in Nigeria,

Soninke and

Wolof in Senegal.

In

Java,

Indonesia,

batik predates written records. G. P. Rouffaer argues that the

technique might have been introduced during the 6th or 7th century from

India or Sri Lanka.

On the other hand, JLA. Brandes (a Dutch archeologist) and F.A.

Sutjipto (an Indonesian archeologist) believe Indonesian batik is a

native tradition, regions such as

Toraja,

Flores,

Halmahera, and

Papua, which were not directly influenced by Hinduism and have an old age tradition of batik making.

Rouffaer also reported that the

gringsing pattern was already known by the 12th century in

Kediri,

East Java. He concluded that such a delicate pattern could only be created by means of the

canting (also spelled

tjanting or

tjunting;

pronounced [ˌtʃanˈtiŋ]) tool. He proposed that the canting was invented in Java around that time.

The carving details of clothes wore by

Prajnaparamita,

the statue of buddhist goddess of transcendental wisdom from East Java

circa 13th century CE. The clothes details shows intricate floral

pattern similar to today traditional Javanese batik. This suggested

intricate batik fabric pattern applied by

canting already existed in 13th century Java or even earlier.

In Europe, the technique is described for the first time in the

History of Java, published in London in 1817 by Sir Thomas

Stamford Raffles who had been a British governor for the island. In 1873 the Dutch merchant

Van Rijckevorsel gave the pieces he collected during a trip to Indonesia to the ethnographic museum in Rotterdam. Today

Tropenmuseum houses the biggest collection of Indonesian batik in the

Netherlands.

The Dutch were active in developing batik in the colonial era, they

introduced new innovations and prints. And it was indeed starting from

the early 19th century that the art of batik really grew finer and

reached its golden period. Exposed to the

Exposition Universelle at Paris in 1900, the Indonesian batik impressed the public and the artisans.

After the independence of Indonesia and the decline of the Dutch textile industry, the Dutch batik production was lost. The

Gemeentemuseum,

Den Haag contains artifacts from that era.

Due to globalization and industrialization, which introduced automated techniques, new breeds of batik, known as batik cap (

[ˈtʃap]) and batik print emerged, and the traditional batik, which incorporates the hand written

wax-resist dyeing technique is known now as batik tulis (lit: 'Written Batik').

At the same time, according to the

Museum of Cultural History

of Oslo, Indonesian immigrants to Malaysia brought the art with them.

As late as the 1920s Javanese batik makers introduced the use of wax and

copper blocks on Malaysia's east coast. The production of hand drawn

batik in Malaysia is of recent date and is related to the Javanese batik

tulis.

In Sub Sahara Africa, Javanese batik was introduced in the 19th

century by Dutch and English traders. The local people there adapted the

Javanese batik, making larger motifs, thicker lines and more colors. In

the 1970s, batik was introduced to the aboriginal community in

Australia, the aboriginal community at Erna bella and Utopia now develop

it as their own craft.

Culture

In one form or another, batik has worldwide popularity. Now, not only

is batik used as a material to clothe the human body, its uses also

include furnishing fabrics, heavy canvas wall hangings, tablecloths and

household accessories. Batik techniques are used by famous artists to

create batik paintings, which grace many homes and offices.

Indonesia

The Javanese aristocrats

R.A. Kartini in

kebaya and her husband. Her skirt is of batik, with the parang pattern, which was for aristocrats. Her husband is wearing a

blangkon

Depending on the quality of the art work, craftsmanship, and fabric

quality, batik can be priced from several dollars (for fake poor quality

batik) to several thousand dollars (for the finest

batik tulis halus which probably took several months to make). Batik tulis has both sides of the cloth ornamented.

In Indonesia, traditionally, batik was sold in 2.25-metre lengths used for kain panjang or

sarong for

kebaya dress. It can also be worn by wrapping it around the body, or made into a hat known as

blangkon.

Infants are carried in batik slings decorated with symbols designed to

bring the child luck. Certain batik designs are reserved for brides and

bridegrooms, as well as their families. The dead are shrouded in

funerary batik.

Other designs are reserved for the Sultan and his family or their

attendants. A person's rank could be determined by the pattern of the

batik he or she wore.

For special occasions, batik was formerly decorated with gold leaf or dust. This cloth is known as

prada

(a Javanese word for gold) cloth. Gold decorated cloth is still made

today; however, gold paint has replaced gold dust and leaf.

Batik garments play a central role in certain rituals, such as the

ceremonial casting of royal batik into a volcano. In the Javanese

naloni mitoni

"first pregnancy" ceremony, the mother-to-be is wrapped in seven layers

of batik, wishing her good things. Batik is also prominent in the

tedak siten ceremony when a child touches the earth for the first time. Batik is also part of the

labuhan ceremony when people gather at a beach to throw their problems away into the sea.

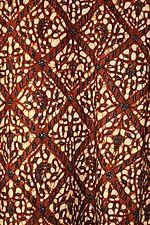

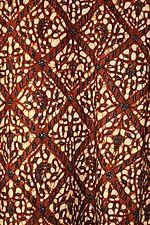

Contemporary men batik shirt in typical Solo style,

sogan color and

lereng motif.

The wide diversity of patterns reflects a variety of influences,

ranging from indigenous designs, Arabic calligraphy, European bouquets

and Chinese phoenixes to Japanese cherry blossoms and Indian or Persian

peacocks.

Contemporary batik, while owing much to the past, is markedly

different from the more traditional and formal styles. For example, the

artist may use etching, discharge dyeing, stencils, different tools for

waxing and dyeing, or wax recipes with different resist values. They may

work with silk, cotton, wool, leather, paper, or even wood and

ceramics.

Popularity

In Indonesia, batik popularity has had its tidings. Historically, it

was essential for ceremonial costumes and it was worn as part of a

kebaya dress, which was commonly worn every day. According to Professor Michael Hitchcock of the

University of Chichester

(UK), batik "has a strong political dimension. The batik shirt was

invented as a formal non-Western shirt for men in Indonesia in the

1960s, not long after the country's birth.

[10]

It waned from the 1960s onwards, because more and more people chose

western clothes as fashionable, decimating the batik industry.

However, batik clothing has revived somewhat in the turn of 21st

century, due to the effort of Indonesian fashion designers to innovate

batik by incorporating new colors, fabrics, and patterns. Batik is a

fashion item for many young people in Indonesia, such as a shirt, dress,

or scarf for casual wear.

Kebaya

is regarded as a formal attire for women. It is also acceptable for men

to wear batik in the office or as a replacement for jacket-and-tie at

certain receptions. After the UNESCO recognition for Indonesian batik as

intangible world heritage on October 2, 2009, Indonesian administration

has asked Indonesians to wear batik on Friday, and wearing batik every

Friday is encouraged in all government offices and private companies

ever since.

Batik had helped improve the

small business

local economy, batik sales in Indonesia had reached Rp 3.9 trillion

(US$436.8 million) in 2010, an increase from Rp 2.5 trillion in 2006.

The value of batik exports, meanwhile, increased from $14.3 million in

2006 to $22.3 million in 2010.

The existence and use of batik was already recorded in the 12th

century and the textile has since become a strong source of identity for

Indonesians,

and to lesser extent Malaysia and Singapore. Batik is featured in their national airlines uniform, the flight attendants of

Singaporean,

Garuda Indonesia and

Malaysian

national airlines wear batik prints in their uniform. Although the

uniforms are actually not real batik because the production is not using

the traditional way but using mass produced techniques. The female

uniform of Garuda Indonesia flight attendants is more authentic modern

interpretations of kartini style

kebaya and batik

parang gondosuli motif, which also incorporate

garuda's wing motif and small dots represent

jasmine.

The batik motif symbolizes the ‘Fragrant Ray of Life’ and endows the wearer with elegance.

Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei

Batik was mentioned in the 17th century

Malay Annals. The legend goes when

Laksamana Hang Nadim was ordered by

Malacca King, Sultan Mahmud, to sail to India to buy 140 pieces of

serasah

cloth (batik) with 40 types of flowers depicted on each. Unable to find

any that fulfilled the requirements explained to him, he made up his

own. On his return unfortunately, his ship sank and he only managed to

bring four pieces, earning displeasure from the Sultan.

Today,

Malaysian batik can be found on the east coast of Malaysia such as

Kelantan,

Terengganu and

Pahang, while batik in

Johor clearly shows

Javanese and

Sumatran influences since there are a large number of Javanese and Sumatran immigrants in southern Malaysia.

The most popular motifs are leaves and flowers. Malaysian batik often

displays plants and flowers to avoid the interpretation of human and

animal images as idolatry, in accordance with local Islamic doctrine.

However, the butterfly theme is a common exception. The Malaysian batik

is also famous for its geometrical designs, such as spirals. The method

of Malaysian batik making is different from those of Indonesian

Javanese batik, the pattern being larger and simpler, seldom or never

using the

canting to create intricate patterns, it relies heavily on the

brush painting method to apply colors to fabrics. The colors also tend to be lighter and more vibrant than deep colored Javanese batik.

Thailand

Batik

sarongs are also designed as wraps for casual beachwear. In the southern Thai island of

Koh Samui,

batik is easily found in the form of resort uniforms, or decorations at

many places, and is also used for the locals' casual wear in the forms

of sarongs or shirts and blouses. It is the most common, or even

symbolic product for those visiting Koh Samui Island. The Batik of Samui

mostly shows the beauty and attractions of the paradise island and its

culture, such as the coconut shells, the beaches, palm trees, the

island's tropical flowers, fishing boats, its rich water life and

southern dancer, Papthalung.

Azerbaijan

The batik pattern can be found in its women's silk scarves, known as

kelagai, which have been part of women's clothing there for centuries.

Kelagai were first produced in the village of Basgal and were created

using the stamping method and natural colors. The cocoons were

traditionally processed by women while the hand-printing with hot wax

was only entrusted to male artists. The silk spinning and production of

kelagai in Azerbaijan slumped after the fall of the USSR. It was the

Inkishaf Scientific Center that revived kelagai in the country. Kelagai

is worn by women both old and young. Young women prefer bright colors,

while older women wear dark colors.

China

Batik is done by the ethnic people in Guizhou Province, in the South-West of China. The

Miao,

Bouyei and

Gejia

people use a dye resist method for their traditional costumes. The

traditional costumes are made up of decorative fabrics, which they

achieve by pattern weaving and wax resist. Almost all the Miao decorate

hemp and cotton by applying hot wax then dipping the cloth in an indigo

dye. The cloth is then used for skirts, panels on jackets, aprons and

baby carriers. Like the Javanese, their traditional patterns also

contain symbolism, the patterns include the dragon, phoenix, and

flowers.

Types and Variations of Batik

Sacred Dance of

Bedhoyo Ketawang. The

prada (gilded) batik is wrapped around the body.

Javanese court batik in deep brown color

Cirebon batik depicting sea creatures

Javanese Kraton Batik (Javanese court Batik)

Javanese

kraton (court) Batik is the oldest batik tradition known in Java. Also known as

Batik Pedalaman (inland batik) in contrast with

Batik Pesisiran (coastal batik). This type of batik has earthy color tones such as black, brown, and dark yellow (

sogan),

sometimes against a white background. The motifs of traditional court

batik have symbolic meanings. Some designs are restricted: larger motifs

can only be worn by royalty; and certain motifs are not suitable for

women, or for specific occasions (e.g., weddings).

The palace courts (

keratonan) in two cities in

central Java are known for preserving and fostering batik traditions:

- Surakarta (Solo City) Batik. Traditional Surakarta court batik is preserved and fostered by the Susuhunan and Mangkunegaran courts. The main areas that produce Solo batik are the Laweyan and Kauman districts of the city. Solo batik typically has sogan as the background color. Pasar Klewer near the Susuhunan palace is a retail trade center.

- Yogyakarta Batik. Traditional Yogya batik is preserved and fostered by the Yogyakarta Sultanate and the Pakualaman

court. Usually Yogya Batik has white as the background color. Fine

batik is produced at Kampung Taman district. Beringharjo market near Malioboro street is well known as a retail batik trade center in Yogyakarta.

Pesisir Batik (Coastal Batik)

Pesisir batik is created and produced by several areas on the

northern coast of Java and on Madura. As a consequence of maritime

trading, the Pesisir batik tradition was more open to foreign influences

in textile design, coloring, and motifs, in contrast to inland batik,

which was relatively independent of outside influences. For example,

Pesisir batik utilizes vivid colors and

Chinese motifs such as clouds,

phoenix,

dragon,

qilin,

lotus,

peony, and floral patterns.

- Pekalongan Batik. The most famous Pesisir Batik production area is the town of Pekalongan in Central Java

province. Compared to other pesisir batik production centers, the batik

production houses in this town is the most thriving. Batik Pekalongan

was influenced by both Dutch-European and Chinese motifs, for example the buketan motifs was influenced by European flower bouquet.

- Cirebon Batik. Also known as Trusmi Batik because that is the primary production area. The most well known Cirebon batik motif is megamendung (rain cloud) that was used in the former Cirebon Kraton. This cloud motif shows Chinese influence.

- Lasem Batik. Lasem batik is characterized by a bright red color called abang getih pithik (chicken blood red). Batik Lasem is heavily influenced by Chinese culture.

- Tuban Batik. Batik gedog is the speciality of Tuban Batik, the batik was created from handmade tenun (woven) fabrics.

- Madura Batik. Madurese Batik displays vibrant colors, such as yellow, red, and green. Madura unique motifs for example pucuk tombak (spear tips), also various flora and fauna images.

Indonesian Batik from other areas

Java

- Priangan Batik or Sundanese Batik is the term proposed to identify various batik cloths produced in the "Priangan" region, a cultural region in West Java and Northwest Java (Banten). Traditionally this type of batik is produced by Sundanese people in the several district of West Java such as Ciamis, Garut, an Tasikmalaya; however it also encompasses Kuningan

Batik which demonstrate Cirebon Batik influences, and also Banten Batik

that developed quite independently and have its own unique motifs. The

motifs of Priangan batik are visually naturalistic and strongly inspired

by flora (flowers and swirling plants) and fauna (birds especially

peacock and butterfly). The variants and production centers of Priangan

Batik are:

- Ciamis

Batik. Ciamis used to rival other leading batik industry centers in

Java during early 20th century. Compared to other regions, Ciamis batik

is stylistically less complex. The flora and fauna motifs known as ciamisan

are drawn in black, white, and yellowish brown. Motifs are similar to

coastal Cirebon Batik, but the thickness of coloring share the same

styles as inland batik. The thick coloring of Ciamis batik is called sarian.

- Garut Batik. This type of batik is produced in the Garut district of West Java. Garutan batik can be identified by its distinctive colors, gumading

(yellowish ivory), indigo, dark red, dark green, yellowish brown, and

purple. Ivory stays dominant in the background. Despite applying

traditional Javanese court motifs such as rereng, Garut batik uses lighter and brighter colors compared to Javanese court batik.

- Tasikmalaya

Batik. This type of batik is produced in the Tasikmalaya district, West

Java. Tasikmalaya Batik has its own traditional motif such as umbrella. Center of Tasikmalaya Batik can be found in Ciroyom District about 2 km from city center of Tasikmalaya.

- Kuningan Batik.

- Banten Batik. This type of batik employs bright and soft pastel colors. It represents a revival of a lost art from the Sultanate of Banten,

rediscovered through archaeological work during 2002-2004. Twelve

motifs from locations such as Surosowan and several other places have

been identified.

- Java Hokokai Batik. This type is characterized by flowers in a

garden surrounded by butterflies. This motif originated during the Japanese occupation of Java in the early 1940s. The long fabrics usually is done in two pattern called pagi/sore

(Indonesian: morning and afternoon) refer to two type of motifs in one

sheet of fabric, as the solution of cotton fabrics scarcity during war

time. Another recognizable traits of Java Hokokai batik are the Japanese

influenced motifs; such as sakura (cherry blossoms) and seruni or kiku

(chrysanthemums, Japan national flower and the symbol of the emperor),

butterflies (symbol of female elegance in Japanese culture), and

overlaying intricate details that has made Jawa Hokokai batiks as one of

the most notable, noble and beautiful batik art forms in Asia.

-

Javanese batik with bird and floral motifs

-

Batik Buketan Pekalongan shows European flower bouquet

-

Batik Lasem with its typical bright red

-

Batik Java Hokokai demonstrated Japanese influenced motifs

Bali

- Balinese

Batik. As Balinese Hindu culture does not restrict the depiction of

images, the Balinese have traditionally focused more on sculpture and

painting than on textiles. Balinese batik was influenced by neighbouring

Javanese Batik and is relatively recent compared to the latter island,

having been stimulated by the tourism industry

and consequent rising demand for souvenirs (since the early 20th

century). In addition to the traditional wax-resist dye technique and

industrial techniques such as the stamp (cap) and painting, Balinese batik sometimes utilizes ikat (tie dye).

Balinese batik is characterized by bright and vibrant colors, which the

tie dye technique blends into a smooth gradation of color with many

shades.

Sumatra

- Jambi Batik. Trade relations between the Melayu Kingdom

in Jambi and Javanese coastal cities have thrived since the 13th

century. Therefore, the northern coastal areas of Java (Cirebon, Lasem,

Tuban, and Madura) probably influenced Jambi in regard to batik. In

1875, Haji Mahibat from Central Java revived the declining batik

industry in Jambi. The village of Mudung Laut in Pelayangan district is

known for producing Jambi batik. This Jambi batik, as well as Javanese

batik, influenced the batik craft in the Malay Peninsula.

- Minangkabau Batik. Minangkabau ethnic also have batik called as Batiak Tanah Liek

(Clay Batik). They use clay as dye for batik. The fabric was immersed

in clay for more than 1 day to make permanent color and after that they

design the motif of animal and flora

- Aceh Batik.

- Palembang Batik.

- Riau Batik.

Painting

Out of its traditional context as fabrics with pattern, batik can also be as a medium for artists to make traditional or modern

paintings or artworks. Such arts can be categorized in the normal categorization of arts of the west.

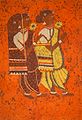

-

Batik painting depicting two Indian women

-

Javanese batik painting depicting buddhist deity

-

-

Indonesian modern batik painting.

-

-

Batik Collectors

- Santosa Doellah has been recognised by The Indonesian Museum of

Records as having the world’s largest collection of ancient

Chinese-influenced Indonesian batik textiles. In total his collection

consists of approximately 10,000 Batik pieces.

- The late mother of United States president Barack Obama, Ann Dunham was an avid collector of Batik. In 2009, an exhibition of Dunham's textile batik art collection (A Lady Found a Culture in its Cloth: Barack Obama's Mother and Indonesian Batiks) toured six museums in the United States, finishing the tour at the Textile Museum.

- Nelson Mandela wears a batik shirt on formal occasions, the South Africans call it a Madiba shirt.

Technique

-

Batik painting in Java during

colonial period. Observe many different varieties of patterns used.

-

-

-

-

Bambang Oetoro demonstrates batik painting technique in the first batik gallery in

Amsterdam, 1977.

Melted

wax (Javanese:

malam) is applied to cloth before being dipped in dye. It is common for people to use a mixture of

beeswax and

paraffin

wax. The beeswax will hold to the fabric and the paraffin wax will

allow cracking, which is a characteristic of batik. Wherever the wax has

seeped through the fabric, the dye will not penetrate. Sometimes

several colours are used, with a series of dyeing, drying and waxing

steps.

Thin wax lines are made with a tjanting, a wooden handled tool with a

tiny metal cup with a tiny spout, out of which the wax seeps. After the

last dyeing, the fabric is hung up to dry. Then it is dipped in a

solvent

to dissolve the wax, or ironed between paper towels or newspapers to

absorb the wax and reveal the deep rich colors and the fine crinkle

lines that give batik its character. This traditional method of batik

making is called

batik tulis.

For batik prada, gold leaf was used in the Yogjakarta and Surakarta

area. The Central Javanese used gold dust to decorate their prada cloth.

It was applied to the fabric using a handmade glue consisting of egg

white or linseed oil and yellow earth. The gold would remain on the

cloth even after it had been washed. The gold could follow the design of

the cloth or could take on its own design. Older batiks could be given a

new look by applying gold to them.

Industrialization of Technique

Batik cap (copper block stamp) as a method to apply wax on fabrics

The application of wax with a

tjanting tool is done with great

care and therefore is very time-consuming. As the population increased

and commercial demand rose, time-saving methods evolved. Other methods

of applying the wax to the fabric include pouring the liquid wax,

painting the wax with a brush, and putting hot wax onto pre-carved

wooden or copper block (called a

cap or

tjap) and

stamping the fabric. The tjanting is used like a pen on the cloth.

The invention of the

copper block (

cap)

developed by the Javanese in the 20th century revolutionized batik

production. By block printing the wax onto the fabric, it became

possible to mass-produce designs and intricate patterns much faster than

one could possibly do by using a

tjanting.

Batik print is the common name given to fabric that incorporates batik pattern without actually using the

wax-resist dyeing

technique. It represents a further step in the process of

industrialization, reducing the cost of batik by mass-producing the

pattern repetitively, as a standard practice employed in the worldwide

textile industry.

Woodcraft

is a wonderful hobby that can relieve stress and give your mind a new

dimension to creativity. Whether you’re an amateur or a professional

wood craftsman, one thing continues to be a cause for concern is running

out of ideas or less in mastering the science of wood.

Woodcraft

is a wonderful hobby that can relieve stress and give your mind a new

dimension to creativity. Whether you’re an amateur or a professional

wood craftsman, one thing continues to be a cause for concern is running

out of ideas or less in mastering the science of wood.